Press Room

Our children are not chattel for tribal governments – nor will we allow them to be treated as ‘collateral damage’ in the political game of tribal sovereignty any longer.

Summary:

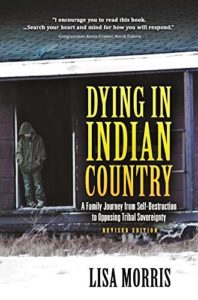

“Dying in Indian Country,” – the true family story of an American Indian who realized welfare policies within tribal and federal government were destroying his extended family.

Recommended by Dr. William B. Allen, Emeritus Professor, Political Science, MSU and former Chair of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights (1989), who has called the book, “…truly gripping, with a good pace.”

Radio Interview

Chuck Morse Speaks: Interview with Elizabeth Morris, Tuesday, December 10, 2013, concerning rampant child abuse on several Indian reservations while federal government, afraid of “stepping on toes,” looks the other way.

~ Interview Audio~

Events:

Child Abuse Continues Unchecked In Indian Country

Is The BIA Another Corrupt Bureaucracy?

Fargo, ND, June 9, 2013 – In memory of Chippewa tribal member Roland J. Morris, Sr., the Christian Alliance for Indian Child Welfare (CAICW) is sponsoring an essay contest on June 9-15, 2013, to draw attention to the widespread and ongoing physical and sexual abuse of children living within Indian Country. The topic of the contest is ‘Why Children Are More Important Than Politics’ with a subtopic of ‘Why Is Our Federal Government Ignoring Ongoing Child Abuse?’ for more information, please visit CAICW.org

About the author:

Elizabeth was raised in the Twin Cities, lived on two reservations, a Bible College campus, and in three small towns. Beth married a member of the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe and has six children. She has a B.A. in Christian Ministries, Diploma of Bible & Missions and is a Registered Nurse.

Press release:

Dying in Indian Country

The true story of an American Indian who realized just how much tribal and federal government policies were destroying his extended family.

Roland grew up watching members of his family die of alcoholism, child abuse, suicide, and violence on the reservation. Like many others, he blamed all the problems on “white people.” Beth Ward grew up in a middle class home in the suburbs. Raised in a politically left family, she also believed that all problems on the reservation originated with cruel treatment by settlers and the stealing of land. Meeting her husband, her first close experience with a tribal member, she stepped out of the comfort of suburban life into a whole new, frightening world.

After almost ten years of living with his alcoholism and the terrible dangers that came with it, they both realized that individual behavior and personal decisions were at the root of a man’s troubles, including their own, and no amount of entitlements would change that.

What cannot be denied is that a large number of Native Americans are dying from alcoholism, drug abuse, suicide, and violence. The reservation, a socialistic experiment at best, pushes people to depend on tribal and federal government rather than God, and to blame all of life’s ills on others. The results have been disastrous.

Roland realized that corrupt tribal government, dishonest federal Indian policy, and the controlling reservation system had more to do with the current pain and despair in his family and community than what had happened 150 years ago.

Here is the plain truth in the eyes of one family, in the hope that at least some of the dying in Indian Country — physical, emotional, and spiritual — may be prevented.

Dr. William B. Allen, Emeritus Professor, Political Science, MSU and former Chair of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights (1989) has called the book, “…truly gripping, with a good pace.”

Meet the author at an online book signing, Saturday, October 13,th, 3 pm eastern time, 12 noon Pacific.

The book sells for $29.99 and is available online. For more information about the author and book, please visit https://dyinginindiancountry.com/

###

Sample page:

Chapter one: May, 1980

It had just turned daylight when we pulled the yellow Chevy station wagon into the small town of Cass Lake. The morning was dawning warm and sunny. Roland was driving. I had been sleeping in the front seat next to him, and his nephew Matthew and Matthew’s girlfriend were sleeping in the back seat. Roland drove through the treeless streets of the tribal tract housing and pulled into the dirt driveway of a yellow house. It was early, but the sun was already beating down. It was going to be a hot day.

Roland honked his horn. Out of a rundown shed from back behind the house, a heavy woman with long black hair emerged unsteadily and stood in its doorway. Roland called her over to the car. Coughing, Annie unsteadily crossed the grass and came up next to the driver’s side. The smell of alcohol wafted through the window. They greeted each other and Roland asked where the wake was being held.

“Up to Bug school,” she said, and then bent her head to throw up on the ground. Roland averted his eyes and patiently waited. Lifting her head, Annie and Roland spoke briefly again before he said good-bye and pulled the car back out of the driveway.

The wake was in a small building at Bug-a-ne-ge-shig school in a shady, wooded area known as “Mission.” I felt very uncomfortable as we pulled up. It was easy to ride in a car going somewhere, but now we were here. I was now far away from home and knew no one but Roland. Numbly, I climbed out of the car. I had never been around many Indian people before. How should I act?

As we entered the dark building I stayed close to Roland. A quick glance around the room showed me I was the only white person there. Many people milled about talking to each other in the main room. Feeling out of place, I avoided looking at anyone and said nothing. Roland moved through the crowd to the kitchen. Hands sweating, I stiffly followed. The women in the kitchen were busy preparing food for the feed that would follow the service. Roland greeted his sister and introduced me.

“Elaine, this is Beth.” Elaine looked up from her work and said hello. She and Roland spoke for a moment, Roland motioned to me, and I tensely shadowed him back into the main room.

He led me through the crowd toward a miniature casket placed alone by the wall. I actually felt some relief as I trailed him. Standing at the casket would be easier than standing apart in the crowd. Roland took a moment at the casket and then stepped aside for me to see. Looking down I saw a precious sleeping child, a small, dark haired girl in a pretty little dress, no more than two years old. Lying peacefully, if you ignored her bruised and battered face.

Roland had told me earlier that his niece had died from a fall from the couch onto a cement floor, but as I looked down at the bruises on both sides of her face, I wondered if that were true.

Turning from the casket, Roland moved toward a tall, slim young man. James, he told me, was his nephew and the father of the little girl. For a short time they whispered together. Roland then turned to me, “Wait here while I go outside to talk to James alone.” But afraid to stay inside surrounded by strangers, I followed them out and sat on the stoop, nervously watching and waiting as Roland and James walked down the dirt driveway and then out onto the dusty road. My eyes followed Roland as long as he was still visible through the trees. As he disappeared, two men emerged from inside and stood a short distance away as they shared a cigarette. How does one sit, what does one look at, what does one do with their hands when one is isolated, alone and out of place? It seemed an eternity before Roland returned, although I knew it was just a short time.

The tiny cemetery was in a heavily forested area near a lake. We followed other cars down a long, narrow, muddy road to get there. Circling through the cemetery, there was nowhere to park. The small area was packed with cars and people. We drove back down the road a ways until we found a spot and then walked back up to the crowd.

At the edge of the crowd, we stood some distance from the ceremony. The graveside service was brief. As it ended and the first shovel of dirt was thrown into the small hole, the baby’s mother, Gloria, let out a loud wail and hung on to James, sobbing.

Roland nudged and we began walking back to the car. As I stepped over yesterday’s puddles, I glanced back at the slowly dispersing crowd.

What happened to that baby girl? I wondered, why won’t Roland tell me what happened?

©2012-2020 – No reproduction or duplication full or in part without permission of author